Master the repository pattern in Typescript

Introduction

During my time at Spendesk, a company that later became a unicorn, I faced a common problem: SQL queries and ORM models were scattered throughout the codebase, leading to a disorganized and difficult-to-maintain system.

It was then that I discovered the repository pattern, which seemed like an ideal solution to our problem.

I started implementing the pattern at Spendesk, working closely with my team to iterate and refine our usage of the pattern over several months.

In the end, we developed a solid implementation that effectively improved our system’s maintainability.

Since then, I’ve continued to apply the repository pattern in other projects and found it to be a valuable tool for keeping codebases clean, organized, and scalable.

This post is the result of my experience playing around with the pattern over the years with other experienced engineers.

The examples we’ll use in this post will be based on an e-commerce application, making it easier to relate the concepts to real-world scenarios.

Core Concept

Domain

A domain refers to a specific area of activity or subject matter within a business organization. It encompasses the knowledge, processes, and rules that are specific to that area or subject matter. For instance, if we are developing an application to sell goods online, the domain is e-commerce.

The e-commerce domain has sub-domains. Here are few of them

- Product management: product descriptions, prices, images, and inventory levels.

- Payment processing: accepting credit card payments, PayPal, or other payment methods

- Shipping and delivery: calculating shipping costs, tracking delivery status, and communicating with shipping carriers

Entities

An entity is an object that represents a real-world concept or object in the domain.

In an e-commerce application, an entity might be a Product, a Customer, or an Order.

Aggregates

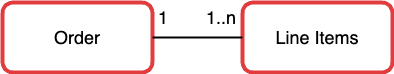

An aggregate is a collection of related entities that are treated as a single unit. This can be visualized as a tree, where the root is the single entry point.

For example, in an e-commerce application, orders and line items are both entities that are linked together. An order may have one or many line items, but these line items only make sense in the context of that particular order.

Therefore, the aggregate in this case is the order.

Consistency boundaries

An aggregate is the consistency boundary, also known as transactional boundary. This means that any changes made to the aggregate must be consistent and atomic, so that the aggregate remains in a valid state at all times.

In our e-commerce application, an order consists of multiple line items, each with its own amount and quantity.

If a change is made to one of these line items, it’s important to ensure that the order’s total amount is updated accordingly.

The repository pattern

The importance of aggregates

When data is stored and retrieved from the storage medium without proper structure, it results in mixed and disorganized code that is difficult to name and communicate about.

Identifying the aggregates of an application is critical

- for avoiding data inconsistencies (consistency boundaries)

- because it represents the real life things, that are easy to talk about and manipulate. And it keep the code aligned with the domain.

An order is an order. A customer is a customer.

But an object with an id, a customer email and an order date represents nothing in the domain.

Keep domain and storage logics appart

Combining domain and storage logics result in a number of issues.

The code is hard to test

Testing becomes difficult due to the need to mock query building libraries or ORMs. At Spendesk, we were using Sequelize, a JavaScript ORM. It was challenging to mock because the output values were not simple plain objects.

The storage representation of the data

The storage representation of data can be different, particularly in the case of SQL where an aggregate may be split across several tables.

For example, an e-commerce application may have an orders table and a line_items table to store each item of an order (as it’s a one to many relationship). This constraint should not appear in the domain logic.

Polluted domain logic

Instead of having a clear logic that simply reflect the domain rules, the domain logic is polluted with the storage logic.

Moreover, changes made to the storage can then potentially affect the domain logic.

Introducing the repository pattern

The previous points underline how important it is to

- define entities and aggregates that reflect real world entities, and enforce their use

- separate the domain and storage logics

The repository pattern is the solution.

A repository is a component that encapsulate the storage logic of an aggregate.

The repository acts as a mediator between the domain logic of the application and the data access layer. It provides a set of methods for performing data operations, such as get, upsert, and delete, as well as other specific queries that the application may require.

By using the repository pattern, the application code is decoupled from the data access layer, which makes it easier to switch to a different data storage system or to make changes to the data access layer without affecting the rest of the application code.

It also makes it easier to unit test the application code, since the repository can be mocked easily.

Consistency boundaries

The repository implementation must ensure that all operations performed on the aggregate are atomic. In a SQL implementation, this can be achieved using SQL transactions. By wrapping all SQL queries in the same transaction, it’s possible to ensure that if any query fails, all the other queries will be reverted, preventing inconsistencies in the data.

Software architecture and repositories

Software architecture layers

You may be familiar with clean architecture or hexagonal architecture.

Regardless of how your project is architectured, you should have at least a separation between the domain and the infrastructure details, as explained before.

The medium of storage should not affect the domain logic, because the domain logic doesn’t know and is not related to a particular medium of storage. Orders can be stored in a file, a relational database, or in RAM: in does not matter, the domain logic remains the same.

The infrastructure layer is responsible for providing access to the underlying technology, such as databases, message queues, and web services. It acts as a bridge between the domain layer and the underlying technology stack, enabling the domain layer to interact with the underlying resources without being tightly coupled to them.

To decouple the domain from the infrastructure, the domain will define and expose an interface that describe the persistence needs for a particular aggregate.

An implementation of this interface can be built for a particular medium of storage (a PostgreSQL database for instance) in the infrastructure layer. This implementation might be injected in the domain. The domain doesn’t know which implementation it is (that is PostgreSQL behing), but it does not matter.

Implementing aggregates

Entity services

In Typescript, two options are available for implementing aggregates

- object-oriented programming (OOP) using classes

- plain objects

In either approach, an entity service will be required to apply business logic and call the repository.

The difference is that with OOP, the domain logic will be encapsulated into the entity class. While with plain objects, the domain logic will be in the entity service.

In OOP, the domain logic must not be in the entity service, as this goes against OOP principles. Instead, the domain logic will be encapsulated in the entity class.

In the contrary, for plain objects, the business logic must be in the entity service, as plain objects are not capable of encapsulating domain logic: they are just structs.

Let’s see 2 examples, one using OOP, and another one using plain objects.

Both examples will use a simplified product entity, with only a name and a price. They focus on updating the product price. The business rule is that the product price must be greater than 0.

Using plain objects

interface Product {

id: string;

name: string;

price: number;

}

const buildProductService = (dependencies: Dependencies) => {

const { productRepository } = dependencies;

const updateProductPrice = async (

id: string,

price: number

): Promise<UpdatePriceResult> => {

// first, the product is fetched from the repository

const product = await productRepository.get(id);

// if the product can't be found, then an explicit business error is returned

if (!product) {

return { outcome: "notUpdated", reason: "productNotFound" };

}

// make sure the price is greater than zero,or return an explicit business error

if (price <= 0) {

return { outcome: "notUpdated", reason: "priceLowerOrEqualZero" };

}

// update the price of the entity

product.price = price;

// upsert the entity in the repository to persist the new price

await productRepository.upsert(product);

return { outcome: "updated" };

};

return { updateProductPrice };

};

Using classes

The big difference is that price verification and update has been moved inside the Product class.

class Product {

private id: string;

private name: string;

private price: number;

constructor(id: string, name: string, price: number) {

this.id = id;

this.name = name;

this.price = price;

}

// the product entity has a method to set the price

public setPrice(newPrice: number) {

// make sure the price is greater than zero,or return an explicit business error

if (newPrice < 0) {

return { outcome: "notUpdated", reason: "priceLowerOrEqualZero" };

}

// update the price of the entity

this.price = newPrice;

return { outcome: "updated" };

}

}

const buildProductService = (dependencies: Dependencies) => {

const { productRepository } = dependencies;

const updateProductPrice = async (

id: string,

price: number

): Promise<SetPriceResult> => {

// first, the product is fetched from the repository

const product = await productRepository.get(id);

// if the product can't be found, then an explicit business error is returned

if (!product) {

return { outcome: "notUpdated", reason: "productNotFound" };

}

// call the setter

const updateResult = product.setPrice(price);

if (updateResult.outcome === "notUpdated") {

return updateResult;

}

// upsert the entity in the repository to persist the new price

await productRepository.upsert(product);

return { outcome: "updated" };

};

return { updateProductPrice };

};

Complete typescript example

Let’s take a look at a complete definition and implementation of an aggregate and its associated repository, using plain objects.

For the purpose of this example, we will once again use the order aggregate, this time including all of its attributes.

Domain layer

Starting from the domain is a natural approach, as it forms the foundation of the application.

It is crucial to build the domain around business constraints rather than technical ones.

First, define the business entity

- Each order must have a unique identifier.

- An order belongs to a customer.

- The date when the order was placed should be stored.

- An order can be cancelled, subject to certain conditions.

- An order can contain multiple items:

- Each item corresponds to a product in the catalog.

- The price of the item should be stored, even if the product has a price because the product price may change over time.

- The same product can be ordered multiple times within the same order.

- The total amount of the order should be calculated as the sum of all the items in the order.

Here is one way to define the aggregate

export type LineItem = {

id: string;

productId: string;

quantity: number;

price: number;

};

export type Order = {

id: string;

customerId: string;

orderDate: Date;

totalAmount: number;

lineItems: LineItem[];

cancellationDate?: Date;

};

Define persistence needs for this aggregate

Given the defined order aggregate, here are the persistence needs

- The order’s unique identifier will be referenced in various places (such as shipping), so it must be possible to retrieve an order by its ID.

- Retrieve all orders associated with a specific customer.

- It’s possible for an order to be updated in some cases (such as when it’s cancelled).

Here is a possible interface for this repository.

interface Orders {

getById: (id: string) => Promise<Order | undefined>;

getByCustomerId: (customerId: string) => Promise<Order[]>;

upsert: (order: Order) => Promise<void>;

}

Infrastructure layer

Now that everything is defined, let’s write a PostgreSQL implementation for this repository.

CREATE TABLE orders (

id uuid PRIMARY KEY,

customer_id int NOT NULL,

order_date timestamp NOT NULL,

cancellation_date timestamp NOT NULL,

total_amount numeric(10,2) NOT NULL

-- FOREIGN KEY (customer_id) REFERENCES customers (id)

);

CREATE TABLE line_items (

id uuid PRIMARY KEY,

order_id uuid NOT NULL,

product_id int NOT NULL,

quantity int NOT NULL,

price numeric(10,2) NOT NULL,

FOREIGN KEY (order_id) REFERENCES orders (id)

-- FOREIGN KEY (product_id) REFERENCES products (id)

);

import { Knex } from "knex";

import { Order, LineItem, Orders } from "../../../domain/order";

interface PostgresqlOrderRepositoryDependencies {

db: Knex;

}

type OrderRow = {

id: string;

customer_id: string;

order_date: Date;

cancellation_date?: Date;

total_amount: number;

};

type LineItemRow = {

id: string;

order_id: string;

product_id: string;

quantity: number;

price: number;

};

const transformOrderRowToOrder = (

orderRow: OrderRow,

lineItemRows: LineItemRow[]

): Order => {

return {

id: orderRow.id,

customerId: orderRow.customer_id,

orderDate: orderRow.order_date,

cancellationDate: orderRow.cancellation_date,

totalAmount: orderRow.total_amount,

lineItems: lineItemRows.map((lineItem) => ({

id: lineItem.id,

productId: lineItem.product_id,

quantity: lineItem.quantity,

price: lineItem.price,

})),

};

};

const transformOrderToOrderRow = (order: Order): OrderRow => {

return {

id: order.id,

customer_id: order.customerId,

order_date: order.orderDate,

cancellation_date: order.cancellationDate,

total_amount: order.totalAmount,

};

};

const transformLineItemsToLineItemRows = (

orderId: string,

lineItems: LineItem[]

): LineItemRow[] => {

return lineItems.map((lineItem) => {

return {

id: lineItem.id,

order_id: orderId,

product_id: lineItem.productId,

quantity: lineItem.quantity,

price: lineItem.price,

};

});

};

export const buildPostgresqlOrderRepository = (

dependencies: PostgresqlOrderRepositoryDependencies

): Orders => {

const { db } = dependencies;

const getById = async (id: string): Promise<Order | undefined> => {

const orderRows = await db

.select("*")

.from<OrderRow>("orders")

.where("id", id);

if (orderRows.length === 0) {

return undefined;

}

const lineItemRows = await db

.select("*")

.from<LineItemRow>("line_items")

.where("order_id", id);

return transformOrderRowToOrder(orderRows[0], lineItemRows);

};

const getByCustomerId = async (customerId: string): Promise<Order[]> => {

const orders = await db

.select("*")

.from<OrderRow>("orders")

.where("customer_id", customerId);

const ordersItems = await db

.select("*")

.from<LineItemRow>("line_items")

.where(

"order_id",

orders.map((order) => order.id)

);

return orders.map((order) =>

transformOrderRowToOrder(

order,

ordersItems.filter((item) => item.order_id === order.id)

)

);

};

const upsert = async (order: Order): Promise<void> => {

await db.transaction(async (trx) => {

await trx("orders").upsert([transformOrderToOrderRow(order)]);

await trx("line_items").upsert(

transformLineItemsToLineItemRows(order.id, order.lineItems)

);

});

};

return { getById, getByCustomerId, upsert };

};

Note that the interface is called Orders and not OrderRepository. The reason is a DDD reason: in the domain, “repository” means nothing. We would say “retrieve the order 1 from the orders”, not “retrieve the order 1 from the order repository”.

A few best practices to finish strong

Naming

The repository

The repository interface name should be the name of the aggregate, in plural. For instance, the repository interface for the Order aggregate is called Orders. Because it represents all the orders.

The name of the repository implementation must contains the storage medium specifications.

The function responsible for building a PostgreSQL implementation of the repository Orders can be named buildPostgresqlOrderRepository.

The methods

A repository must be seen as a collection of data, similar to a Set.

In such a collection, there is no create method, since the creation of an entity is handled by the business logic. The repository’s role is to receive the entity from the business logic and persist it.

Similarly, cancel is not a valid method neither. The cancelOrder method could be part of the orderService as it’s the business logic that actually modifies the order to effect the cancellation. The repository’s responsibility is simply to receive the order and persist its updated version.

export const buildOrderService = (

dependencies: OrderServiceDependencies

): OrderService => {

const { orderRepository } = dependencies;

// ...

// cancel order is part of the order service

const cancelOrder = async (id: string): Promise<CancelOrderResult> => {

const order = await orderRepository.getById(id);

if (!order) {

return { outcome: "notCancelled", reason: "orderNotFound" };

}

if (order.cancellationDate) {

return { outcome: "notCancelled", reason: "alreadyCancelled" };

}

// the cancellation is done by setting the cancelledAt date to the current date

order.cancellationDate = new Date();

// then, the repository upsert method is called to persits the change

await orderRepository.upsert(order);

return { outcome: "cancelled" };

};

// ...

return {

cancelOrder,

// ...

};

};

Ids and Timestamps

In a SQL database, it’s possible to generate values for certain fields when defining the schema of a table.

For instance, ID SERIAL PRIMARY KEY (or AUTO INCREMENT) will generate an ID for newly inserted rows. In most ORMs, timestamps like created at are automatically added to each row using things like DEFAULT CURRENT TIMESTAMP.

However, when working with the order aggregate, it’s important not to generate values for the id and order date fields in the storage medium.

-

These fields are business values. The id is used to uniquely identify the entity in the business logic, while the order date represents the date on which the order was created in the business logic, not the date at which the row was inserted in the storage medium.

-

The repository handle the persistence of the aggregate order, which includes the id and order date fields. So it must be set by the business logic

-

In theory, there can be multiple implementations of a repository interface. These implementation are distinct, so there is no way to ensure there is no

IDconflict between the 2 repository.

Imagine if both repository implementation start the id value at 1 and increment the id counter after each insert. The same id will match different entities stored in 2 distinct repositories.

Here is the rule:

- if the value is a business value, it must be set in domain layer

- if the value is only used in the storage, it must be generated in the storage medium

Partial read, partial write, and performance

To cancel an order, the only attribute to update is the cancellation date.

Similarly, there may be cases where only certain attributes of an order are needed, such as the order dates for a customer.

In these situations: should there be methods that return or update only the relevant attributes ?

As already mentioned, a repository must be seen as a collection of objects, like a Set or a Map.

In such collections, the full object is fetched or set, not just a part of it. The same holds true for repositories.

Furthermore, an Order is an Order. A subpart of an Order is not an Order, and it can be difficult to name because it doesn’t represent anything meaningful in the domain.

Most of the time, the reason people want to do partial updates or partial gets is for performance reasons. Few extra attributes will not significantly impact the performance an application. And in most cases, code readability is more important than performance.

If there is actually a performance problem with a repository, the first step would be to assert that the aggregates and business logic are well defined.

Otherwise, the CQRS pattern can be beneficial in cases where there are performance issues, as it aims to separate the reading and writing responsibilities in a system.

By separating these concerns, a write model can handle commands and modify the state of the aggregate with well-defined business logic, while the read model can be optimized for queries and return denormalized data that is tailored to the client’s needs.

By doing so, this approach can result in significant performance improvements.

Concurrent update

Suppose that two upserts are made at the same time on the same order.

- A fetches the order

- B fetches the order

- A changes the cancellation date, and calls the

upsertmethod - B changes the total amount, and calls the

upsertmethod.

Although no errors occur, the cancellation date ends up being set back to null. How can this be prevented from happening?

One solution to this problem is to use version numbers, though it may not be the best approach for every situation

Each entity in the system would be assigned a version number, which is incremented by one every time an update is made to the entity.

When the update method is called on the repository to persist the new version of the entity, the update should be performed based on both the entity’s ID and version number (rather than ID only). Since the version number has been incremented, the entity to be updated should be the one with the previous version (i.e. version number minus one). If no match is found, it means that at least one update has been made to the entity in the meantime, and the repository should return an error.

At this point, the business logic must determine how to handle the situation - automatic retry or returning an error are two possible options.

Testing the business logic

In memory repository implementation

Setting up a database for testing can be complicated, slow, and unnecessary when the purpose is to test the business logic. Instead of injecting an instance of a PostgreSQL implementation, it is possible to inject an instance of an in-memory implementation, which is much simpler and faster.

The in-memory implementation can be created using a Set or a Map, and does not require any additional setup.

// still an OrderRepository, but using a Map instead of a PostgreSQL database as storage medium

export const buildInMemoryOrderRepository = (): OrderRepository => {

// use a Map to store the orders by id

const ordersById = new Map<string, Order>();

const getById = async (id: string): Promise<Order | undefined> => {

const order = ordersById.get(id);

return order;

};

const getByCustomerId = async (customerId: string): Promise<Order[]> => {

const orders = Array.from(ordersById.values());

return orders.filter((order) => order.customerId === customerId);

};

const upsert = async (order: Order): Promise<void> => {

ordersById.set(order.id, order);

};

return { getById, getByCustomerId, upsert };

};

import { buildOrderService, Order } from "../index";

import { buildInMemoryOrderRepository } from "../../../infrastructure/repositories/order/inMemory";

// example of a unit test, testing the order service method cancelOrder, and using the in memory repository

describe("cancelOrder", () => {

const orderRepository = buildInMemoryOrderRepository();

const orderService = buildOrderService({ orderRepository });

describe("given the id of an existing order", () => {

describe("given the order is already cancelled", async () => {

const id = "order1";

const order: Order = {

id,

customerId: "customerId",

orderDate: new Date(),

cancellationDate: new Date(),

totalAmount: 100,

lineItems: [

{

id: "lineItem1",

productId: "product1",

price: 50,

quantity: 2,

},

],

};

await orderRepository.upsert(order);

it("returns an error because the order is already cancelled", async () => {

const result = await orderService.cancelOrder(id);

expect(result).toEqual({

outcome: "notCancelled",

reason: "alreadyCancelled",

});

});

});

// other tests ...

});

// other tests ...

});

Isolate the business logic

The in-memory repository is unnecessary because it does not add value to the test - it is only present because a repository must be injected. The focus of the test should be on the business logic, not the repository. In addition, a poorly implemented in-memory repository may affect the test results, and writing tests to evaluate a repository implementation that is solely used for testing purposes can be excessive.

To test the system effectively, it is best to isolate the business logic and test it independently. If the aggregates are implemented as classes, testing the class methods may be sufficient, since the business logic is contained within the class. On the other hand, if the business logic is primarily located in the entity service, it may be useful to extract that logic into functions that are not exposed outside of the service, but only used for testing purposes.

Conclusion

The repository pattern is a powerful tool for software engineers seeking to create maintainable, scalable, and organized codebases. Its ability to separate concerns and decouple domain logic from underlying data storage implementations makes it a powerful technique that enforces aggregate usage, prevents the contamination of business logic with storage logic, and makes testing easier.

Throughout this post, we have explored essential concepts and best practices for implementing the repository pattern in TypeScript, using a real-world e-commerce application as our example. From defining the repository interface and aggregates to implementing concrete repositories, we have covered a wide range of topics that will aid in mastering the repository pattern.

Whether you are a seasoned developer or just beginning, I hope this post has given you a solid foundation for building better software using the repository pattern.